Time, Existence and Questions without Answers

These concepts are quite complex and I am not smart enough to fully avoid mistakes in understanding and conveying them. Especially during write-up mistakes in formulation slip through, please correct me where I am wrong, discuss, counter-argue and feel free to ask questions. I am sure that I did not explain all of this to the degree that these fascinating topics deserve.

2025, a new year has just begun. Not few left before AGI or Doom. But as they say, may you live in interesting times!

We all know what a year is, right? 365 Days and +1 for a leap year. And a day? 24 hours, an hour 60 min… We can go on further spiraling down in timescale without explaining a thing. I encounter this pattern of recursive or even circular answers quite often when asking or while arguing, which can be tiring.

But there are questions where this kind of reasoning seems so inevitable in first sight that the question itself feels gödelian. With gödelian I mean that the question itself is conceptually similar to the Gödel sentence in Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem: It is constructable (askable), “true” (the question makes sense), but unprovable and sometimes seemingly unanswerable in any consistent manner.

We are limited

It is easy to construct a question for which no logically consistent answer exists.

Asking about a perfect prediction of the future state of the universe is one of them. But it is not “gödelian”, it is logically provable that it is not answerable:

A part of the system can never fully understand the system it is part of. Our universe contains everything causally entangled with us, including us as we are fully embedded in it by definition. You can not predict everything including yourself, as the prediction process itself would have to be predicted. In other words, the set of all sets cannot contain itself, which it would need to compute the next step (See the Barber Paradox for intuition or Russell’s Paradox proving that the set of all sets can not contain itself). Computing the next step is the only way to guarantee perfect prediction as shown by computational irreducibility.

Btw, many of these standpoints have fundamental implications for philosophical themes, such as free will but these are topics for another post.

Today I want to bend your mind by asking these seemingly gödelesque questions:

- Why does logic exist a priori?

- Why/How can Time exist?

- Why/How does anything exist?

Logic

I can reason in different ways, I am not sure if you find any argument alone sufficient.

We know something is true under certain axioms, if we derived it using logic. Without logic we can not derive knowledge. Without knowledge we can not reason, we can not perceive, we can not predict future states, we can not survive.

Logic is untouchable, as arguing against it uses the principles of logic one tries to defeat.

If you do not think that existence is built on pure logic you instantly close any further thinking about it. You in general stop existing, no perception, no thought, nothing, just void. (It still gets confusing as you can not argue such a claim in any direction. As arguing uses logic, it circles either way).

I think the statement “Logic does not exist” is in this way the most Gödelian sentence we can get in natural language.

Why Computationalism

Computation is the only paradigm we found that is safe against Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems as it uses states and is solely constructive in nature, unlike many branches of mathematics where operations modifying infinite elements in a set at once are allowed.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems show that in any sufficiently expressive and consistent formal system, there exist statements that are true but unprovable within the system. This highlights the inherent limitations of formal systems which non-computational paradigms cannot circumvent. These limitations stem from the unrestricted self-reference and abstraction allowed in stateless, axiomatic frameworks such as traditional mathematics.

In contrast, computation operates through finite, discrete processes, where state transitions ensure that the system avoids paradoxical forms of self-reference. This constructiveness naturally avoids the issues highlighted by Gödel’s theorems.

Gödel’s Theorem shows that we can always construct a logical statement in a non-computational language which is true but inside the system neither provable as true or false. An incomplete system is insufficient for describing existence and the universe’s fundamentals because it cannot account for all truths within its framework, leaving key aspects undecidable. Such undecidability undermines consistency and coherence, making it unreliable as a foundation for modeling reality. Computation, with its constructive and state-based nature, avoids these pitfalls, ensuring a robust framework free from unresolvable paradoxes, as we simply cannot construct undecidable statements in it.

This is roughly why I assume Computation as the base of everything that can exist.

Symbolizing this shift of thought: \(\pi\) is a function not a number.

Time

When we talk about time we use units stacked on top of each other. We can measure time by utilizing mechanical systems with a constant update, such as clocks. Atomic clocks are the most precise, they work by exploiting the consistent oscillations of atoms as they transition between energy states, yielding a reliable interval which we can map to our time units.

At least since Einstein’s Theory of Relativity we know that time is not globally constant, but relative, it fully depends on the velocity (special relativity) and position (general relativity) in space and is therefor combined in one concept: spacetime.

This observation also makes sense from a computational viewpoint: Time Dilation is a consequence of, inter alia, assuming particles are stable patterns moving through a space structure, such as the spatial hypergraph in Wolfram Physics (think of vortices in water or more precisely gliders in Conway’s Game of Life).

“If the object moves, then in effect it has to be “re-created at a different place in space”—and this process takes up a certain number of rewritings, leaving fewer for the intrinsic evolution of the object itself, and thus causing time to effectively “run slower” for it.”

- Explanation cited from Wolfram’s article ‘On the Nature of Time’ (must-read, it is really good!)

But time to an observer is not directly the rewriting/updating of the spatial hypergraph, it forms through causal events, while computational irreducibility ensures that it is one-way from the perspective of an observer: The past has to be compressed with loss (see Russell’s paradox), making it impossible to go reverse, while the future is not fully predictable (see computational irreducibility). If it were, the concept of time for an observer would vanish as all future states would be already known and no separation between now and future would exist.

We see that time can only exist because of change. Time does not exist in a static system. We also see that time is emergent due to our own computational boundedness. Not being able to jump ahead, unable of having unlimited memory and knowledge about the whole universe, entails time. For a system filling out all of space, the concept of space does not exist. For a system filling out all of time by being able to jump ahead (due to computational irreducibility), time would not exist as a concept.

So we are stuck with the property of change.

How can change be derived from first principles?

This question is confusing. As explained before, we as computationally bounded observers cannot think outside of change. Computation is made out of state transitions under rules, at least this is how we can think of it.

In principle a computational rule entails the whole structure. So in essence, a computational rule already determines everything following from it. The only reason why we use change (the transition of states by applying the rule) is because we are computationally bounded. There are rules which are computationally reducible, for those, time is not a concept needed, as we can jump ahead. An example are fractals, where we can exploit repetitions and constant patterns.

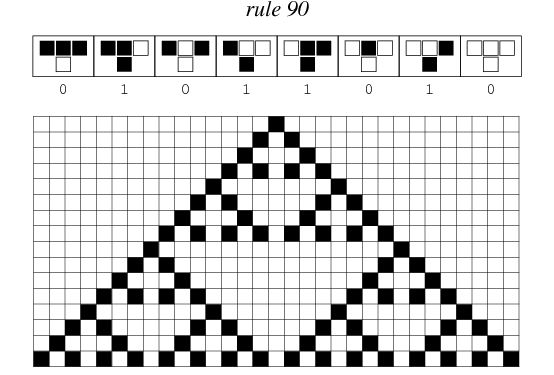

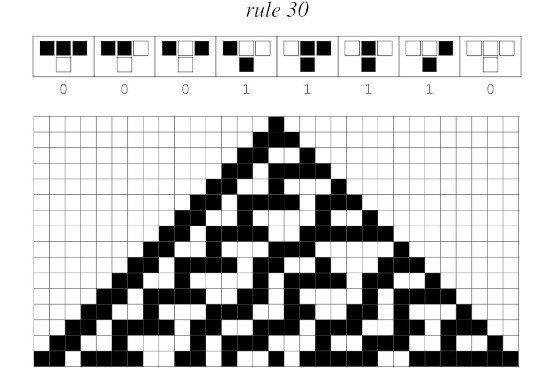

1D cellular automata, states are stacked along the y-axis (each next row representing the next state, source: Wolfram MathWorld)

Finite computations stopping at a certain step, which we can fit in our memory, also do not need to be thought of in change. We can just plot them as a finite thing, assuming they are short enough.

All computational systems exist and are determined. These concepts exist as platonic objects in the realm of logic, independent of whether someone finds them or thinks of them. They can be discovered and will be the same every time, just as a irrefutable consequence of the initial condition, pre-existing without needing invention.

So in the end change is a frame of reference we can not escape from when reasoning about our universe, we are limited in computational power and therefor time emerges. For the whole computational structure, change does not exist. Change just exists as a concept for substructures inside of the greater whole. The Ruliad, the entangled limit of all possible computation is a static structure if seen from outside, but as nothing can exist outside of it the concept of change does not go away in our reasoning.

Existence

And another confusing topic for which I should write a dedicated post…

We assume the computational paradigm, so we can say that something can exist if it can be implemented, meaning it can be constructed in a finite amount of computational steps.

But it can also not exist, right? so why does anything exist then?

Why does anything exist?

Similar to the other questions, we can only try to reason through and make educated guesses, but it is especially hard to answer the question of “how anything exists”. The question of “why do we exist in this specific universe” some may lazily answer with the Anthropic principle, without explaining the assumption of anything existing in the first place.

Any answer to this question, has to make sure it does not make assumptions about anything, as otherwise you just move the question one layer lower. We need to answer the question in such a way that we do not assume anything, no axioms. Impossible? Maybe not, hear me out.

If we assume something, we constrain the space of possibilities. When we ask the question why anything exists, we imply that the default is non-existence. That there is something, that has to change for existence. From this perspective we can not remove all assumptions.

But what about possibilities just existing as possibilities? Existence is defined only in contrast to non-existence and vice versa. If we do not set any assumptions, all possibilities exist independently in parallel: One branch of non-existence (nothing in there to ponder) and all branches of possible computational systems (initial conditions + rules).

The infinite possibilities reduce and entangle from a functional perspective for Turing-complete systems which by the Church-Turing Thesis are all computationally equivalent. Some start conditions lead to others in other systems, entangling all computational systems in one object, the only real singleton, existing just by possibility as no axioms can be assumed:

The Ruliad, the only thing that must exist without priors, a platonic singleton containing everything that is computationally possible.

(Keep in mind that we did not use computation as an unjustified axiom here, we derived it as the only viable option we have)

Final words

If you came this far, you are probably not the kind of person who only considers thinking about questions and answers that have obvious utility.

Many might say that these topics are not to be pondered, as some questions, like the one of existence, might be unprovable, and more important not of clear relevance for science.

They are probably correct in pointing that out, but to me this is not primary, these questions and ideas are intrinsically beautiful to me. And it is still useful pondering these questions, as they sharpen our thinking, epistemology, ontology and likely enable us to discover new techniques and ideas adoptable to science.

I hope you enjoyed it! :)

Further sources

- Stephen Wolfram’s great article ‘On the Nature of Time’

- A great meme by Joscha Bach about the concept of truth, touching most and even additional topics of this post: Notions of Truth meme (find his verbose explanation here)

- Another way of trying to explain existence: Zero Ontology

- An iai podium discussion which reminded me to write about this: The riddle of the beginning